Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

May 7, 2017

Chris Pinard /owlcation.com/

My primary interests center around the folklore, customs, history, and mythology of the Celts, the Germanic speaking peoples, and the Slavs.

Contact Author

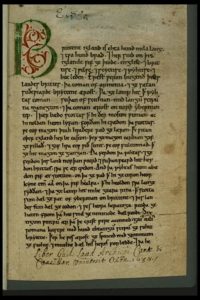

First Page of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle–

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Found within the first sentences of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is an obscure reference to the British people, stating that they originated in Armenia: “The island Britain is 800 miles long, and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh (or British), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward.” Taken by itself, this quote would appear to be somewhat out of place. However, further investigation reveals corroborating evidence for an Anatolian origin.

One must first understand that the people being spoken about here would be the Brythonic speakers (The British). These were the people who lived in England prior to the invasions of the Normans, Vikings, Saxons, and Romans. So then, is there any evidentiary support to indicate that the Britons originated in Armenia? Yes, there is in fact quite a few indications that the British might have origins in the general vicinity

Map of Armenia

Megaliths

An 18th-century clergyman named Richard Polwhele concluded that the British were in fact of Armenian extraction. He stated, “That the original inhabitants of Danmonium were of eastern origin, and, in particular, were Armenians, is a position which may, doubtless, be supported by some show of authority.” Richard was writing at the time when archaeology was just being developed. He based much of his conclusions on the aforementioned passage from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as well as the similarity of structures that dotted Devonshire and Armenia. Specifically, near the city of Sisian is an archaeological site called Carahunge. This locale features stone megaliths that have a similar appearance to the dolmens and stone circles that feature prominently in Britain. While the stones in Britain are far older than the British Celts, they could hint to a more ancient migration.

Carahunge

Brutus and Troy

Conversely, an equally strong tradition adheres to the notion that the British people originated from Troy. Arguably this line of thought may have come into vogue due to influences from the Romans when they occupied Britain. This legend first makes itself known in the 7th-century work by Isidore of Seville titled Etymologiae. A passage in this book advocates the notion that General Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus was the individual who the island of Britain was named after. Undoubtedly he would have come in contact with Celtic people as he subdued Spain. It is theoretically possible that the Celts he came in contact with had some memory of this figure years later after they dispersed into Gaul and later to Britain. However, the book later reiterates the story of a much more famous and legendary Brutus who was present during the fall of Troy.

In the 9th century within the Historia Brittonum, one can find further reference to the Brutus legend. “The island of Britain derives its name from Brutus, a Roman consul. Taken from the southwest point it inclines a little towards the west, and to its northern extremity measures eight hundred miles, and is in breadth two hundred. It contains thirty three cities”. The manuscript further states, “According to the annals of the Roman history, the Britons deduce their origin both from the Greeks and Romans.” This legend would then seem to indicate that whether by Roman influence or by indigenous tradition, the British people felt that their origins lay to the south and east. The manuscript further describes how after the Trojan War Aeneas found his way to Italy. Several generations passed, and Brutus (a descendant of Aeneas) accidentally commits patricide and is forced to flee. He then establishes residence in Gaul, only to later make way to Britain where he establishes a city. This town was then named New Troy (later known as London).

Aeneis Fleeing Troy

Genetic Data and Oral Preservation of Lore

It is unknown if either of these traditions are truly indigenous. However, they bear similarities to the genetic record. As genetic testing has become ever more precise, migrations of ancient people have been determined. Roughly seven to nine thousand years ago a population group migrated to Britain from Anatolia by way of France. In the classical period, Armenia would have been much larger in area than the present day country. In fact, it included portions of eastern Anatolia. Therefore, an Anatolian origin for the British would seem fitting. Further, a German businessman named Heinrich Schliemann located the city of Troy in Anatolia. Thus there is the possibility that the recollection of an Armenian or Trojan origin of the Brits might have come from memories that were preserved through oral tales. However, one must consider how truly ancient that this migration would have been. Would they have been able to preserve the memory of their migration over a period of thousands of years? The answer is yes. Folk memory can be quite conservative. Take for example the 13th-century work of The Nibelungenlied, it is thought that the word Schelch, which is preserved in the document is a reference to the Irish Elk (a species that likely went extinct roughly eight thousand years ago). Another example of how conservative folk memory can be is that the Vedas frequently mention the importance of the Sarasvati river. Eventually, the river dried up. Modern studies have concluded that the system thought to be the Sarasvati ceased to flow roughly four thousand years ago. Therefore, the memory of the river may have been passed down orally thousands of years before being written. Both of the aforementioned examples demonstrate that it is possible that ancient events can be preserved in legends.

Schelch- Ancient Deer Remembered in the Nibelungenlied

Welsh Triads and Iolo Morganwg

The Welsh Triads of Iolo Morganwg might buttress the passage mentioned in Historia Brittonum. They indicate that Brutus did come to Britain and brought Trojan law with him. These triads further detail the respective areas that British tribes came from in Gaul. “There were three social tribes on the Isle of Britain. The first was the tribe of the Cambrians, who came to the Isle of Britain with Hu the Mighty, because he would not possess a country and lands by fighting and pursuit, but by justice and tranquility. The second was the tribe of the Lloegrians, who came from Gascony, and they were descended from the primitive tribe of the Cambrians. The third were the Brython, who came from Armorica, who were descended from the primitive tribe of the Cambrians. These were called the three peaceful tribes because they came by mutual consent and tranquility, and these tribes were descended from the primitive tribe of the Cambrians, and all three tribes had the same language and speech.” While the previous passage proves interesting, it must be taken with a large grain of salt. Iolo Morganwg did use authentic material in many of these triads; however, others are thought to be forgeries. Therefore it is unlikely if the triad in question is authentic. However, If this passage does come from original source material, it could support genetic data that indicates that the largest contributor to British DNA comes from France. In looking at the larger migration pattern, it would appear that these people migrated from Anatolia, across southern Europe into France and spent time there before passing into Britain. This could fit in nicely with the notion that “Brutus” spent time in Gaul. Again, with dates of such a remote period, one must be extremely cautious when looking at these similarities. However, it is interesting that the legend fits the migration pattern.

Iolo Morganwg

An Irish Legend for Comparison

While not conclusive, these origin stories of the British people do point to the possibility that the British people did have some recollection that part of their ancestors came from Anatolia. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the entire legend of Brutus is true. Rather, elements of folk memory were preserved in tales that were later written down. It would then stand to reason that Brutus might simply be a literary figure onto which these memories were grafted. To further support this assertion, one might look to Ireland to see a similar situation.

Genetic data from the Irish Celts indicates an Iberian origin of the people. This too fits in quite well with what the Book of Invasions (An Irish repository of legend) describes. “At last, from a tower in northern Spain (Iberia), Cesaire saw the coast of Ireland in the distance and knew their journey was nearly at an end. They landed in Ireland, in the harbour of Corca Dhuibhne in Kerry.”

Little can be stated for certain with respects to these legends. However, it is intriguing that these similarities between legend and genetic data exist. Unfortunately, it is impossible to determine if any of these passages recorded down faded accounts of the migration of the Brits.

Old Map of Britain

owlcation.com/social-sciences/The-Peopling-of-Britain-Legendary-Origins-in-Anatolia