Turkey’s Dangerous New Exports: Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman Visions and Regional Instability

April 21, 2020 – Marwa Maziad, Jake Sotiriadis:

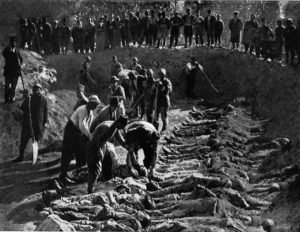

– ARMENIAN GENOCIDE – I REMEMBER AND I DEMAND

There is certainly no shortage of writings on Turkey today regarding that country’s “drift” away from its Western orientation. Some who espouse this argument frame the consequences in terms of Turkey’s increased ties to China.[1] While Turkey itself has launched an “Asia Anew” policy,[2] the outsized focus on this and other alleged signs of Turkey’s “drift from the West” distracts from the very palpable effects of its adventurism in the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey’s increasingly reckless foreign policy is on full display — from weaponizing refugees to extort the European Union to exporting mercenary Jihadist fighters to Libya.[3] These are hardly the actions of a responsible regional power, much less a key member of the NATO alliance.

Taken in total, one might logically conclude that such actions are “irrational,” as they diminish Turkey’s standing in both the region and the world. But if we interpret these dynamics as the consequences of ideology warping a state’s rational self-interest, their underlying rationale becomes less opaque. Unlike other Islamic ideological models, Turkish Neo-Ottomanism focuses on a revival of a “greater Turkey” that renews a classical, civilizational model of the Ottoman Empire’s legacy anchored by economic, military, and political power.[4]

Western media narratives largely ignore these nuances, painting President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as an autocrat who seeks to increase his domestic powerbase in Turkey at any cost. But by this standard alone, then, authoritarianism itself becomes the scapegoat.[5] By contrast, Erdoğan is merely the symptom of a broader problem — that is Ankara’s promotion of a Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman ideology that has dangerous implications for the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East, and beyond. This misguided vision of pan-Islamism evokes a culturally hegemonic form of political Islam (as well as a form of militant Jihadism).

How did Ankara arrive at this juncture? The concept of Pan-Islamism certainly is not a new phenomenon. In historical terms, the Ottoman Empire (1517-1923) represented the last Caliphate and Islamic State. A series of military defeats in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and World War I (1914-1918), followed by a crucial victory in the Turkish War of Independence (or Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922), culminated with the founding of the secular Turkish Republic in 1923. The establishment of the modern Turkish state effectively extinguished traditional Ottomanism as a viable political ideology. In its place, widespread Kemalist reforms generated a seismic shift in Turkish society: the abolition of the Sultanate, adoption of the Latin alphabet in place of Arabic script, and a new legal code modeled after European, not exclusively Islamic principles.[6]

Moreover, following this critical juncture in Turkey’s own history, the Middle East region subsequently witnessed a series of independence movements throughout the early to mid-20th century. These independence movements resulted in the creation of the modern republics of Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and Tunisia, among others. The newly independent regional states largely modeled their governments in the image of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. As such, this unique historical experience and legacy explain the present-day resistance to Turkey’s expansionist, pan-Islamist project by Egypt, along with the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. Turkey’s burgeoning alliance with Qatar and the Muslim Brotherhood as a transnational movement serves to further exacerbate existing tensions. But Ankara’s Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman ideology is essentially drawing new fault lines across the region—pitting statist, secular, republican governance models against the culturally-expansionist, militant, and pan-Islamist alternative in Turkey.

All too often, external interpretations of Neo-Ottomanism are reduced to a euphemism for Turkey’s increasingly “anti-Western” political orientation. To be sure, this phenomenon has little to do with the West and reflects much more about the emerging ideological model in Turkey. While Erdoğan certainly embodies a shift in Turkish politics, the conditions of possibility for his meteoric rise in the early 2000s were established by the re-introduction of Ottomanism during Turgut Özal’s tenure, and later reprised by foreign minister (and academic) Ahmet Davutoğlu. Davutoğlu claimed that Turkey is destined to become a regional hegemon, merging geographic determinism with cultural agency and Turkey’s historical experience.[7] But where Davutoğlu advocated a policy of “zero problems with neighbors,” Erdoğan has managed to create crises with nearly all of Turkey’s neighbors.