December 28 2015

Soldiers are trained to do one thing above all else: follow orders. Soldiers who disobey face the repercussions of insubordination. Louis Dartige Du Fournet, a vice admiral of the French Eastern Squadron that was blockading Ottoman shores near Syria in 1915, was aware of what the consequences could be should he take matters into his own hands. Nonetheless, he ordered the rescue of over 4,000 Armenian men, women and children from certain death in the foothills of Musa Dagh (Mount Moses, also known as Jebel Musa) in what is present-day southeastern Turkey.

Dartige had no idea how his commanding officers would respond to his orders, but he did not wait to find out. He was acutely aware of the bureaucratic nightmare of intervening in such a conflict, but he was too short on time.

The story began in the summer of 1915, when the council of six Armenian-populated villages – Haji Habibli, Kebusiyeh, Vakif, Kheder Bek, Yoghunoluk and Bitias – located in the Suede district, defied Ottoman orders to join deportation marches out of the country. On July 30 some of the Armenian inhabitants obeyed the Ottoman instructions and were eventually killed during death marches to Syrian deserts. Others – a group of over 5,000 Armenians – left their homes and took refuge in the foothills of Musa Dagh, on the northern tip of the Bay of Antioch. There they mounted a valiant military resistance agaist the Ottoman forces.

There were only 600 fighters among the 5,000 Armenians and they had few weapons. But they were determined and well disciplined.

They built temporary fortifications around the foothills of the mountain. Initially, the Armenian fighters resisted heroically, but with dwindling food and ammunition supplies the situation deteriorated quickly.

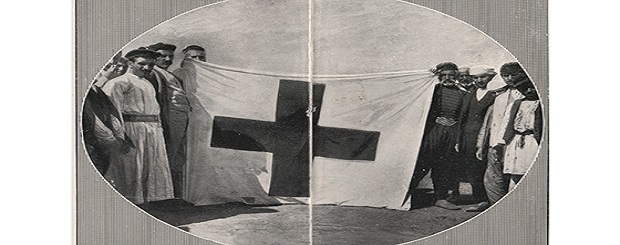

In an attempt to attract the attention of allied warship crews, the fighters raised two flags made out of bed sheets that would be visible from the sea. One of the flags bore a red cross, the other had “Christians are in danger” written on it. They also made bonfires around the flags, hoping to draw attention.

As Vice Admiral Dartige du Fournet wrote in his diary on September 6, 1915, he “received a telegram reporting on this and immediately sailed in this direction on Jeanne d’Arc.” The next day Jeanne d’Arc approached the coast on a reconnaissance mission. Tigran Andreasyan, one of the Armenian leaders, came onboard and asked for at least the civilians – women, children and the elderly – to be evacuated. He was once again promised that French navy would help.

“I realized that we had to help these miserable people,” du Fournet wrote in his diary. He sent an emergency telegram to the high command, but was still extremely concerned about the complex bureaucracy back in France.

At the risk of tarnishing his career, he gave the order to send all cruisers at his disposal to Musa Dagh to begin evacuations immediately.

In his own words, “The time was scarce and whatever they [the high command] told us, it was necessary to evacuate all of them.”

On September 10, 1915, on the 41st day of the resistance, two French warships began bombing Ottoman positions around Musa Dagh in a cover operation. On September 12, five French cruisers – Le Guichen, L’Amiral Charner, Le Desaix, La Foudre and Le D’Estrées approached the shore, cast anchor and dropped boats. Tiran Tekeyan, an officer of Armenian origin on Le Desaix, coordinated the rescue operation, which lasted three days. First the women, children and the old people were evaculated, then the armed forces.

The total number of those rescued was 4,058. It included 1,563 children, several of whom had been born during the operation itself.

Some children born on board were named Guichen in honor of the first cruiser whose crew had noticed the signal from Musa Dagh.

“There were poor little newborns among them wrapped in towels. The Mussalertsi children were passed from hand to hand through the roar of waves. They pulled through the waters and will never know what kind of danger they managed to escape in reality,” du Founet wrote in his diary.

Three months after the evacuation, Dartige received a response to his initial telegram. It contained only one phrase in French: “Où se trouve mont Moise?” (“Where is Mount Moses?)” This proved that had Dartige chosen to follow military procedures and wait for orders, not a single refugee would have survived.

On October 10, 1915 du Fournet was appointed allied commander in the Mediterranean Sea. In December 1916, after the landing of French soldiers near Athens, Louis Dartige Du Fournet was dismissed. He never had children and married a widow after his dismissal. He lived in a small villa near St. Chamassy in southwestern France. Du Fournet died in 1940 and was buried in St. Chamassy. At the time of his death, and for many decades after, the French population knew nothing about his rescue efforts.

However, in 2010, Tovmas Aintabian, a descendant of a Musa Dagh survivor, conducted an investigation into the vice admiral’s life and discovered the location of his hometown, as well as his tomb. Aintabian contacted the local authorities in St. Chamassy and arranged a joint ceremony to honor his ancestors’ savior. Word of Dartige Du Fournet spread throughout France, with most French television channels and newspapers covering the occasion. A marble sculptured flag depicting the one waved by the freedom fighters was placed on the tomb.

Dartige’s tomb has become a pilgrimage site for both Armenians and French paying homage to the man who risked so much and saved so many.

http://horizonweekly.ca